Rem Koolhaas is one of the world’s leading architects. His firm, OMA, has designed buildings around the world, including the Central Library in Seattle (2004) and Chinese state television’s Beijing headquarters in (2012). He also leads AMO, a ‘research and design studio’ that ‘applies architectural thinking to domains beyond’. Known for their voluminous research documents and studies, such as the now classic, 1,300-page S,M,L,XL (1995), Koolhaas, OMA and AMO have long been inspirations for Virgil Abloh. We brought together the 73-year-old architect and theorist of society, urbanism, living spaces and consumerism with the 37-year-old polymath for a wide-ranging conversation, one that reveals two original thinkers currently shaping the landscape of the world we live in.

Virgil Abloh: I do everything with an architectural way of thinking, using my career in design to focus on a brand. I am creating a dialogue with culture that Louis Vuitton and Kering haven’t been able to understand. This is the next generation of consumers, with their own ways to buy, and ideas of what’s important. In the years between 2009 and now, a new consumerism has emerged.

At my Shanghai store I designed the furniture, too. I was interested in the external structure being the main structure and this hollowed-out feeling. It’s the very first furniture I have produced that is on sale in collectable design spheres. Whether it is taking something with a [Marcel] Duchamp-principle and adding value to an inanimate object, or something else, it’s about making new work with a reference to the past.

Rem Koolhaas: And that furniture is just for the store or can it also be bought?

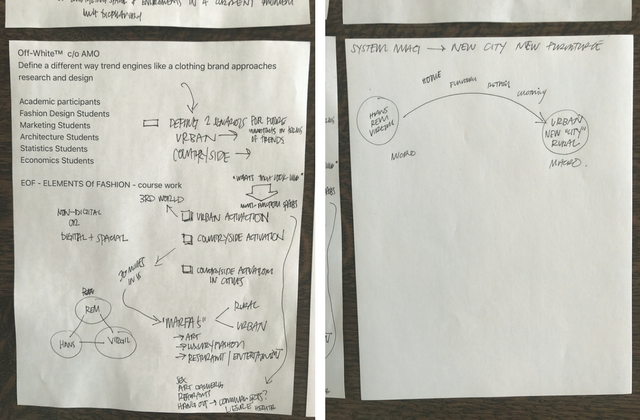

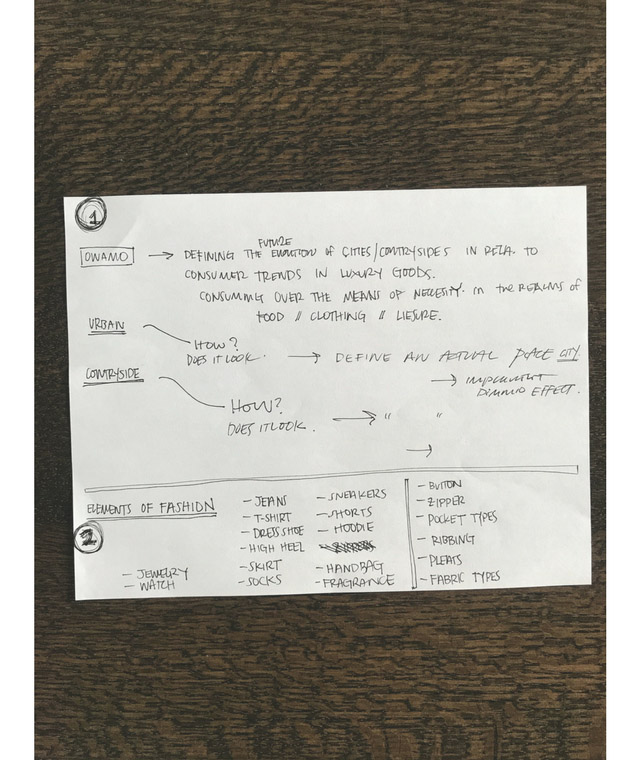

Virgil: Yes, it’s a series you can buy. It was produced in Italy and I have an agent in Paris who represents it globally. My career is fashion four times a year and a new series of furniture maybe once every year and a half. IKEA approached me to do a survey of millennials’ first apartments, so I am looking at doing 30 pieces of furniture that could be a tool kit for millennials. So I am understanding the different clientele — why they purchase furniture, what they want. Part of the study was understanding the Duchamp principles of art and objects. I looked at the IKEA nomenclature, a Kelly bag, and how the price of a Tom Sachs art piece evolves. Looking at Tumblr images is how millennials assemble these images to represent themselves. No one owns anything anymore, but if you have knowledge of a certain chair, then it is part of your dinner conversation. That is the millennials’ train of thought. I am interested in this new cultural world that we have been handed, that processes politics and art in a different and democratic way.

I am doing this survey because I am giving IKEA a design proposal. This is the very frst book that I’ve done as a research project and I wanted to use it in a Duchamp spirit, to reapproach these iconic designs in a way that takes the energy of the historical side and replaces it with something that a young person can identify with. Ultimately, this drove me down the path of researching how the art-gallery world reclaims iconic design pieces.

“I use my career in design to focus on a brand. I am creating a dialogue with culture that Louis Vuitton and Kering haven’t been able to understand.”

Rem: Did IKEA agree to the prices in your design proposal?

Virgil: The prices might be lower! The proposal was to invite people to imagine a college dorm room, and imagine that it contained the equivalent of a $110,000 lamp, say, but because it is made with IKEA, the cost is much lower.

I got interested in plastic, tape and fire-proofing. The images show the disarray in being provocative and pushing IKEA. Now we’re doing prototypes and it all has to be done in a certain way by hand. I find that intriguing because IKEA is a brand that forces the consumer to make the item. It comes with a little Allen wrench, and you have to realise the form through a series of steps. This final form forces people to artistically upholster, which is a process, a DIY, IKEA thing. I want to fnd out what it’s like living with this new idea of preservation.

Rem: So, you say you work with other people, but that you are doing most of this on your own?

Virgil: I embed myself into a culture. It is not simply designing stores for a client, or saying, ‘Here are some chairs for 10,000 student homes’. There is potential for a new way of thinking about introducing new ideas. Within architecture, it’s always been a built form or a published book, those are the arms to seep into the common person. Now I’ve made this brand that speaks to millennials directly. When is our generation going to produce something that is of value to the generation coming afterwards?

Rem: How old are you?

Virgil: I’m 37, which has given me 15 years of practising.

Rem: Do you consider yourself a millennial? Or just before?

Virgil: Just before. I am a little bit too old, but I went to enough school to be able to understand it. I keep myself young — like a fountain of youth!

Rem: Actually, I did the same thing. I went to school again when I was 26 to study architecture.

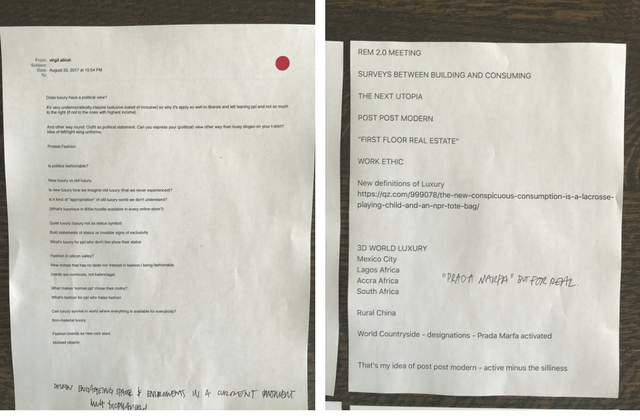

Virgil: I think the Internet has created a sort of utopia. I look at it as potential. Do you feel that this is a Renaissance period or the worst Armageddon?

Rem: I’m not sure I can judge this. I never try to define it. It has elements of both, but I don’t think it is a bad period. Do you? Maybe it just becomes more boring. Cities will become more boring. It will be offces and work. Cities will have no real use. There is no business anymore.

Virgil: I went to a store this morning and there was no one in there, literally no one. Imagine if all the vacant spaces invited contemporary architecture and it was like, ‘Hey, let’s go meet at this pavilion’. An area with Internet and basic things. Just a space that people go to. Space has always had value, but now it means something different. At this moment, once you take things that have traditionally lived in four sacred walls — the art world, the fashion world —this holy layer for purists, and you intersect it with tourists, with people who are authentic to themselves, then you could get change.

I think it could be super profound to come into a home embedded with a new ethos. I have only just scratched the surface. I want to go more in-depth. I want to be part of a think tank on new spaces and collaborate on new, non-traditional projects, finding some way to combine things. I want to create a fashion think tank and write a curriculum. The same way you have set up your infrastructure, I want to do the same thing. I want to do an inverse think tank about consumerism and objects. People invest in clothing but not in the rest of their living space.

At one of my shows, the chairs were called Free Cubes and people could take them. Here’s the shift — people took an Off-White™ product that wasn’t clothing. I never said that they were free and people could leave with them, but people were like, ‘Hey, I can take these’. I broke the threshold. Is this part of the set? Is this going to the trash? Is this going to waste? And their value was raised because I put text on them. I put the word ‘Off’ on them. Kids took three of them, put them in their trunk, rode the subway, and they just ended up in the world. The knowledge of the brand made them take something that wouldn’t be in their closet, but in their living room. Gathering information from millennials and thinking in an architectural way about fashion, there is so much at play between six or seven layers. There is the purist and there is the tourist, who is mindfully following trends on social media.

Rem: You are basically the first person to have something good to say about tourism in 10 years. I’m serious.

Virgil: The young communities of these cities are looking for direction. I want to publish essays of people leaving New York for Los Angeles. That is a huge cultural thing that is happening. It’s a small, infuential story behind why New York has changed in the last fve years. There was a storm that came and wiped out lower Manhattan, and they all decided to go where the weather is constant.

The important rationale about this new youth group is that it feels like they are seeing the world with fresh eyes, as if nothing came before them, trying to rationalise things to make the proper moves forward. Someone who lives with three people might have a living room empty to the point of there being no furniture, because there is no need for them to communally gather. My basis in this project is the bedroom as a unit and what’s absolutely necessary.

Rem: So are you actually looking into conceptualising a new bedroom or a new existence minimum for that age group? Do you know the expression ‘existence minimum’?

Virgil: No.

Rem: It’s the very minimum people need to exist. People find it very frightening because they are addicted to luxury, but I find it very sympathetic. It shows that there is no waste and that you are really focusing on the essential. Is that something you are looking at? Are you trying to do this metaphorically or literally?

Virgil: I am doing it metaphorically. I am interested in the information about this idea of modern living that I have gathered and am discussing with networks. How we live digitally through avatars and Instagram, how we share and connect ideas, and how we’re not really specifc to a city. We are all travelling together, and through our shared decisions there is a trend effect, which dictates and then inspires a whole group of others to continue going down that path. Challenged with the project of designing a set of furniture, designing environments, I am placing importance through discussion on that sort of premise, like the Bauhaus premise. We need to know what is minimal.

“existence minimum refers to the minimum people need to exist. people find that frightening because they’re addicted to luxury, but i find it sympathetic.”

Rem: But, eventually, do you want to construct something?

Virgil: Yes.

Rem: I am actually also working on a project to have a similar pre-fab environment for minimal existence, somewhere in Los Angeles. I didn’t necessarily imagine you were doing this with a physical project, I thought it was stuff that you were developing.

Virgil: Yes, it started out as an aesthetic, but has become more of a survey. It’s turned into travelling the world, interviewing millennials, and finding out how they understand the objects they live with. Where they place importance. How they live with roommates. Then I compare that to the aesthetic assumptions that I had in the beginning.

Rem: And you do that in order to refine them?

Virgil: Yes, exactly. To see if things meet, then refine and reduce.

Rem: To refine it, or to expand it?

Virgil: To refine it. I am interested in editing.

Rem: But you are editing your own furniture line.

Virgil: Exactly.

Rem: So you want to test this.

Virgil: Exactly, to see if my aesthetic ambitions serve a purpose. A large part of the process is understanding what is physically necessary to live as a person who is aged 18 to 26. And then see what adds value to their space from an aesthetic perspective, as well. Hence, the idea of understanding previous notions of furniture, like a Le Corbusier lamp. What I found interesting about the backdrop of IKEA is the role monetary value plays in the overall aesthetic. During my survey, I visited a multimillionaire who had museum-quality art and I wondered what I could make at IKEA that would transcend the idea of monetary value, so that people would adopt it because it is tied to something else with value. It’s research —that’s my point of view and I am having conversations around it to be informed.

Rem: I am very impressed by the aesthetic and I recognise some of the moves, particularly with this material. A return to something that is not blatantly wasteful and almost tender to the touch. I can respond positively to almost all of this, but of course, I do not have the tastes of a millennial.

Virgil: My aggressive ambition is that this state of flux be perfectly ordered because I said, ‘I am going to steer this in the right direction’. My work might alter the actual course that that dart was going to go. It’s all shifting. Is a guy from Silicon Valley going to make the decisions, or me as a guy between architecture and design? I value the work of IKEA and my adding to their ecosystem is about being anti-anonymous design. When I look at all the chairs they offer, they are all designed, which raises this multiplicity of things that look designed, but are not actually provocative. That is where I started with the aesthetic, and then I stopped and began doing this survey to add these dual layers. But it started with me understanding what IKEA is in this world of brands and services.

Rem: You know that IKEA is now, for the frst time, agreeing to dismantle their stores. They are basically stopping their exclusivity.

Virgil: So, yes, I could sell IKEA products at my store.

Rem: Which is a totally new thing.

Virgil: Does IKEA resonate with you, for any specifc thing?

Rem: We consulted with them around 10 years ago, when their stores were in big boxes in the countryside, and they were worried that we were running out of countryside, so they were asking themselves what an urban IKEA would look like. We helped them with that. With many of these companies, you itch to take all their ingredients and take them further, or connect them, or curate them. I feel that this is something that you are doing, or that you want to do, Virgil.

Virgil: You always see IKEA on the way to the airport or into the city. Do you have a term for that? Like, not the full countryside, but that sort of, like, buffer airport zone?

Rem: I am not thinking about that. I think that has been thought about for some time and there is quite a lot of literature.

Now, see Virgil’s latest collaboration with Byredo for Off-White.